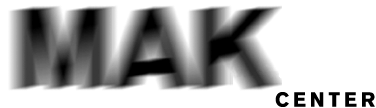

Installation view of Groundswell: Guerilla Architecture In Response To The Great East Japan Earthquake. Photography by Joshua White, 2015.

The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 moved the main island of Japan 8 feet east and shifted the Earth on its axis by estimates of between 4 and 10 inches. The 40-foot-high tsunami that hit the shore 30 minutes later wiped out a 500-kilometer stretch of coastline, and caused the failure of the cooling system at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. More than 20,000 people died and 470,000 lost their homes. Four trains carrying 2,654 people traveling along the Miyagi coastline vanished without a trace.

Groundswell: Guerilla Architecture in Response to the Great East Japan Earthquake displays architecture in action. Frustrated by the slow and inept government response to this natural catastrophe, a number of architects took it upon themselves to address the trauma and rebuilding needs of area residents. Groundswell presented a selection of their efforts as it engaged the ongoing conversation of how architecture can serve communities following a natural disaster. The exhibition featured works by artist Hiroyasu Yamauchi, and architects Hitoshi Abe, Manabu Chiba, Momoyo Kaijima and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (of Atelier Bow-Wow), Senhiko Nakata, Osamu Tsukhashi, and Riken Yamamoto.

About Groundswell

After the tsunami, architects quickly realized that government solutions–such as building massive sea walls to contain future tsunamis–represented blunt force, literal, and ultimately unsatisfactory solutions to a much more complicated problem. It became clear that what was needed was a ground-up, multi-disciplinary platform from which designers, educators, and other experts could work with community members to devise short, medium, and long-term strategies for dealing with these kinds of disasters. Histories, processes, characteristics, and voices of local regions would need to be part of the program. The organization ArchiAid formed from this position, and seeks to provide ways for architects and citizens to think through their domestic and collective space in light of an ever-shifting planet. Most of the projects in Groundswell were developed under the auspices of ArchiAid.

Organized by MAK Center Director Kimberli Meyer and advised by Hitoshi Abe, this exhibition looked at architecture in four ways: as grief work, as collaborative process, as compromise, and as social-geographical event. Grief is powerfully felt in a model of Kesennuma City, one of dozens of models of fallen towns recreated first from research data and then augmented with the memories of former inhabitants. Constructed by Osamu Tsukhashi and students, the model’s color and physical details were supplied by citizens, who also contributed their personal memories of places and events. These were transcribed on small flags that dot the model. Photographs shot by Hiroyasu Yamauchi the day after the tsunami further underscored the emotional devastation wrought by events.

A group effort, A Pattern Book for Reconstruction Planning, is an analysis by architects and planners to help disaster victims understand their towns and homes and create a shared vision for renewal. Developed in a workshop process, the pattern book explores ways in which fishing villagers might like to both recreate and alter their environments. Groundswell presented two main sections of the book, laid out with translations of commentary and explanations. The Core House is a prototype developed from the pattern book workshops and can be seen in photographs and drawings. To date, two of these basic, repeatable homes have been constructed on the Ishimaki peninsula as well as another in Fukushima. The Core House project is led by Momoyo Kaijima and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, principals of Atelier Bow-Wow.

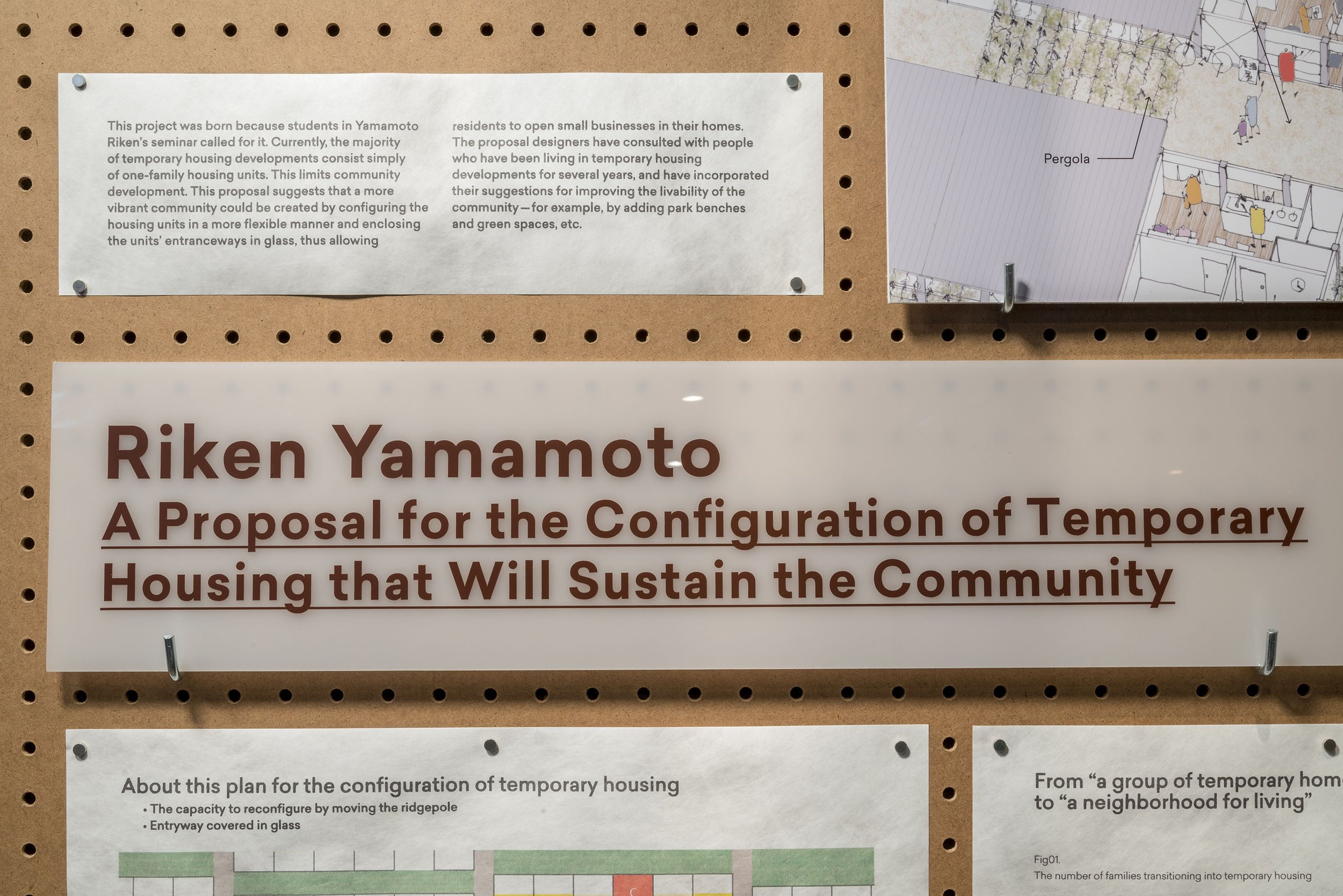

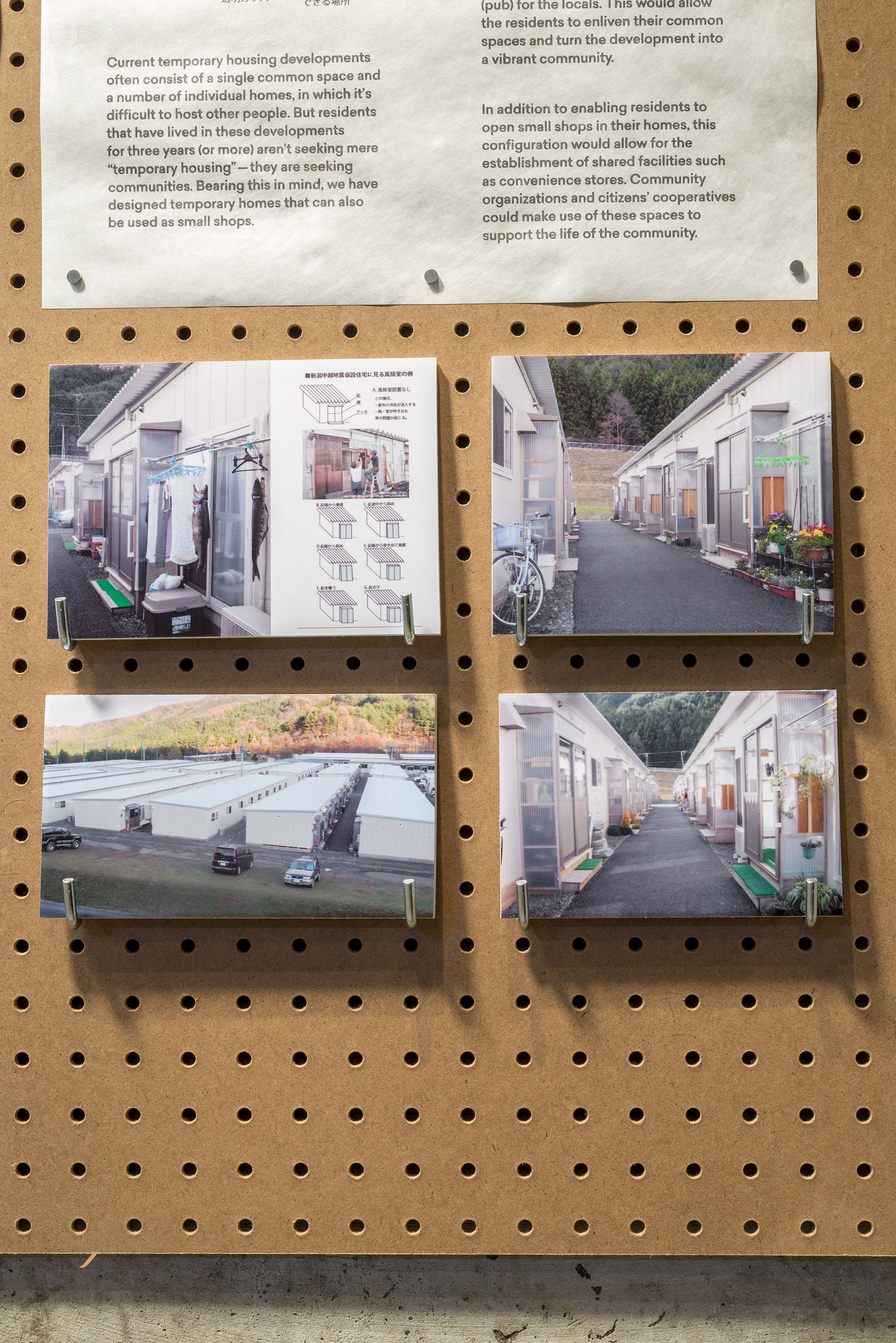

Compromise informs the valiant efforts of architects Hitoshi Abe, Manabu Chiba and Riken Yamamoto in their encounters with both temporary housing and design/build housing towers, both built under the direction of the Japanese government. Here, the unremarkable structures are treated as found objects to be gently but profoundly altered. One of the big problems of these standard building types is that they lack the social spaces key to daily village life, which leads to isolation and eventually a higher suicide rate. Each of the architects transformed the idea of engawa–transition spaces between public and private spheres in traditional Japanese homes that take the form of benches, porches or stoops–into large scale versions that can function for a group of housing blocks. Adding such connective tissue to the austere towers is a simple but successful way to bring crucial design tenets into a system dominated by bureaucracy and value engineering.

Social and geographical interests are seen in the photographic documentation of an annual bicycle tour led by Manabu Chiba through tsunami–affected areas. Promoting tourism and functioning as consciousness raising events, these trips served to make people from other regions–many who had never visited the remote area–familiar with the Oshika Peninsula. Similarly, Senhiko Nakata and his students looked for ways to connect with the displaced coast dwellers. They hit upon the idea to design traditional Japanese towels, made in partnership with the affected communities, and created to benefit tsunami victims. Three annual editions of these collectible towels were on view, and available for purchase.

opening and symposium

As part of opening day activities, the MAK Center at the Schindler House offered a symposium featuring several exhibition participants, as well as design professionals whose work considers similar issues. Presenters included Heather Joy Rosenberg, sustainability consultant, commissioner on the Los Angeles Innovation and Performance Committee, and a US Green Building Council Ginsberg Fellow; Robert M. Arens, Professor of Architecture at California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo; plus featured architects Hitoshi Abe, Manabu Chiba, Senhiko Nakata, and Osamu Tsukhashi. Co-panelists included Frances Anderton, curator of the upcoming Annenberg Space for Photography exhibition Sink or Swim: Designing for a Sea Change, and Amy Murphy, Associate Professor, USC School of Architecture and contributor to New Orleans Under Reconstruction: The Crisis of Planning (Verso, 2014).

Special thanks to exhibition advisor Hitoshi Abe.

Exhibition design by Group Effort: Jessica Fleischmann & Rachel Allen with Dorothy Lin.

This exhibition was made possible by the Japan Foundation, the Terasaki Center for Japanese Studies at UCLA, the Graham Foundation, and the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.